I read in the bathtub and have always loathed e-books, but all that changed a year ago when an e-book publisher bought my debut novel. Since then, I’ve reconsidered my position, put today’s technology in context, and taken some comfort in knowing we’ve been in this kind of maelstrom before.

Two hundred years ago, publishing was a mess. Pirates took work from one country and published it in another, authors cried foul and couldn’t get paid, publishers sprang up out of nowhere to take advantage of the new American mania for reading. Anyone, it seemed, could set up shop.

The publishing free-for-all in the early Republic happened because the booted British no longer could stop the presses if the content disagreed with them. Add to that political revolution an economic one, which was that banks began to lend young, white men money. This was new. Entrepreneurial risk, decried by the Puritans, triumphed as an ethos and the new money policy let sons start businesses without the permission of their conservative elders. Meanwhile, ministers shouted “don’t do it” from the pulpits. New England clergymen hated the novel in particular, with all its multiple points of view and titillating subject matter. They wanted people to keep reading their advice — and maybe also Benjamin Franklin’s.

At the heart of the hoopla, then and now, sat the individual reader. Noah Webster’s runaway best-seller, The Book of Spelling, helped free the reader in those days. Former peasants, farmers with no education, girls as well as boys — any of them felt entitled to pick up the Book of Spelling and study the simple lessons that translated syllabic sounds to letters: the elemental technology of reading. Readers multiplied exponentially.

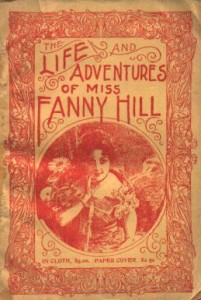

Many of those readers did exactly what the elites feared they would. They read whatever they wanted. After The Bible and their Webster’s, they bought The Coquette, a novel about a wayward woman that swiftly was banned from the new, public libraries. And after The Coquette, at least in some circles, they might read Aristotle’s Masterpiece. This book had nothing to do with Aristotle, the title a diversion to hide the contents: a midwifery manual with explicit instructions on how to make a woman ready to conceive. Down the perceived slippery slope from there was Fanny Hill, an erotic novel that would have been called pornographic if the word had been invented yet (it would take photography and the mass-market printing of the mid 19th century to create that discourse.)

Many of those readers did exactly what the elites feared they would. They read whatever they wanted. After The Bible and their Webster’s, they bought The Coquette, a novel about a wayward woman that swiftly was banned from the new, public libraries. And after The Coquette, at least in some circles, they might read Aristotle’s Masterpiece. This book had nothing to do with Aristotle, the title a diversion to hide the contents: a midwifery manual with explicit instructions on how to make a woman ready to conceive. Down the perceived slippery slope from there was Fanny Hill, an erotic novel that would have been called pornographic if the word had been invented yet (it would take photography and the mass-market printing of the mid 19th century to create that discourse.)

I learned about all this because one of the characters in my novel, The Glass Harmonica, is an itinerant bookseller and he hides from his wife, the heroine-musician, that his trade in illicit books supports their family. Henry struggles with the ethics of his business — both of them believe that sensuality can lead, surprisingly, to virtue instead of vice. Pursuing happiness, they open their senses to commune with what they call the electrical current of life. Of course, this gets them into trouble.

Readers get themselves into and out of trouble vicariously — safely — in books. When we read, we identify with the characters, make choices with them, experience any manner of different lives. And in the end, most books sell not because of smut, as feared by the ministers picturing a ‘slippery slope’, but because one reader tells another: ‘hey, I think you’ll like this.’ Noah Webster experienced this wave. In the parlance of today, his book went viral without him getting paid much for it. And so Noah got political, and he pushed for the invention of royalties, and earned the moniker of the Father of Copyright for his advocacies for professional writers, a new career invented in part by people like him.

Dread over the e-book revolution arises from many sources: Will writers and local bookstores fall to the same fate as musicians and Tower Records? How will people be paid for their work? And what about libraries — now they can buy one hard cover and lend it a hundred times but with they have to buy a new e book copy for each reader appearing at the circulation desk?

The warning that good books will be replaced by slop reminds me of the hand-wringing from those now-distant pulpits. Same story, different century. Readers are the true arbiters and we readers never shut up about a book we like. One person’s slop is another person’s treasure, and those conversations are, if anything, enhanced by this Facebook, worldwide gabfest we’ve invented in the 21st century. We will sort out the business aspects.

The most poignant fear for me is the loss of the familiar, cherished, soft, fluttery paperback in my hands. I sold my novel to an e-book publisher before I’d bought a device, before I even held an e-reader for more than a second in my hands. I leaped for complex of reasons: personal opportunity, infectious inspiration from my publisher, a friend in New Zealand, not New York, whose idea is to create a virtual book village. I found reasons to continue when the process turned out to be like an old-fashioned guild. I was surrounded by people with ‘ink’ on their hands: a designer who hand-painted the cover, an editor tireless through nearly a year of drafts.

All of this felt good, and yet I was still in the bathtub, reading. It’s my character Henry who taught me not to worry about it. We readers can be many readers in one: we can buy smut and we can buy elevating advice. We can read on paper or on screens. It doesn’t matter. What matters is that original technology: sounds turning to letters. Next week, I go on vacation to an island. I am taking my library with me in a tiny tote bag.